I was a somewhat precocious child: a natural bookworm. Before television and video games hijacked my attention, I would blissfully spend an entire Sunday afternoon at the local library, perched in a big chair by a window with a big stack of Asimov, Arthur C Clarke, Conan Doyle, Bradbury, or Pratchett until the shadows crept in and the Librarian put on her jacket and stood waiting for me at the exit. At home, I'd often stay up late reading under my blankets with a flashlight and spend the next day falling asleep in class. I assume all this reading led to my interest in writing. Even though I ended up in a tech career, writing was my first passion, and there was a time when I dreamed about being a novelist.

Early on, I was fortunate to have teachers who valued writing and taught me how to express my thoughts and exercise my imagination through words on paper. I have very fond school memories of making chapbooks with hole-punched pages held together with string in Mr Gallagher’s class when I was seven or eight. My story was about a sailor who ran adrift after an ocean storm and found himself in a land of towering human giants. Okay, it's not very original! And most likely influenced by one of my favorite Saturday morning television shows. But the fun I had narrating and illustrating that little chapbook gave me a hint of how satisfying a writing project could be and motivated me to keep exploring my ability.

When I was thirteen, our local newspaper ran a short story contest for kids and teens. I wrote a fantasy piece about a sick child who dreamed about meeting a faery and a magic grasshopper. It was terribly cliche and overly sentimental, but it won second place and was published in the Sunday edition. This was astonishing to me: my words were in the newspaper where thousands of people in my hometown would see it. People I didn’t even know! The £20 cash prize was a lot for a thirteen-year-old in 1991 but I hardly cared about the money—seeing my name and story in print was pure gold. It also tickled me pink that the newspaper had asked their staff artist to provide an accompanying illustration showing my story's protagonist holding the magic grasshopper in his open hand, how delightful!

It would be a very long time before anyone ever paid me again for my writing, but I went on to study English as my college degree, and I’ve made good use of my writing and communication skills throughout my career. I haven't written a book (yet), but writing is very much an integral part of my adult life, and I am a committed lifelong student of improving my craft.

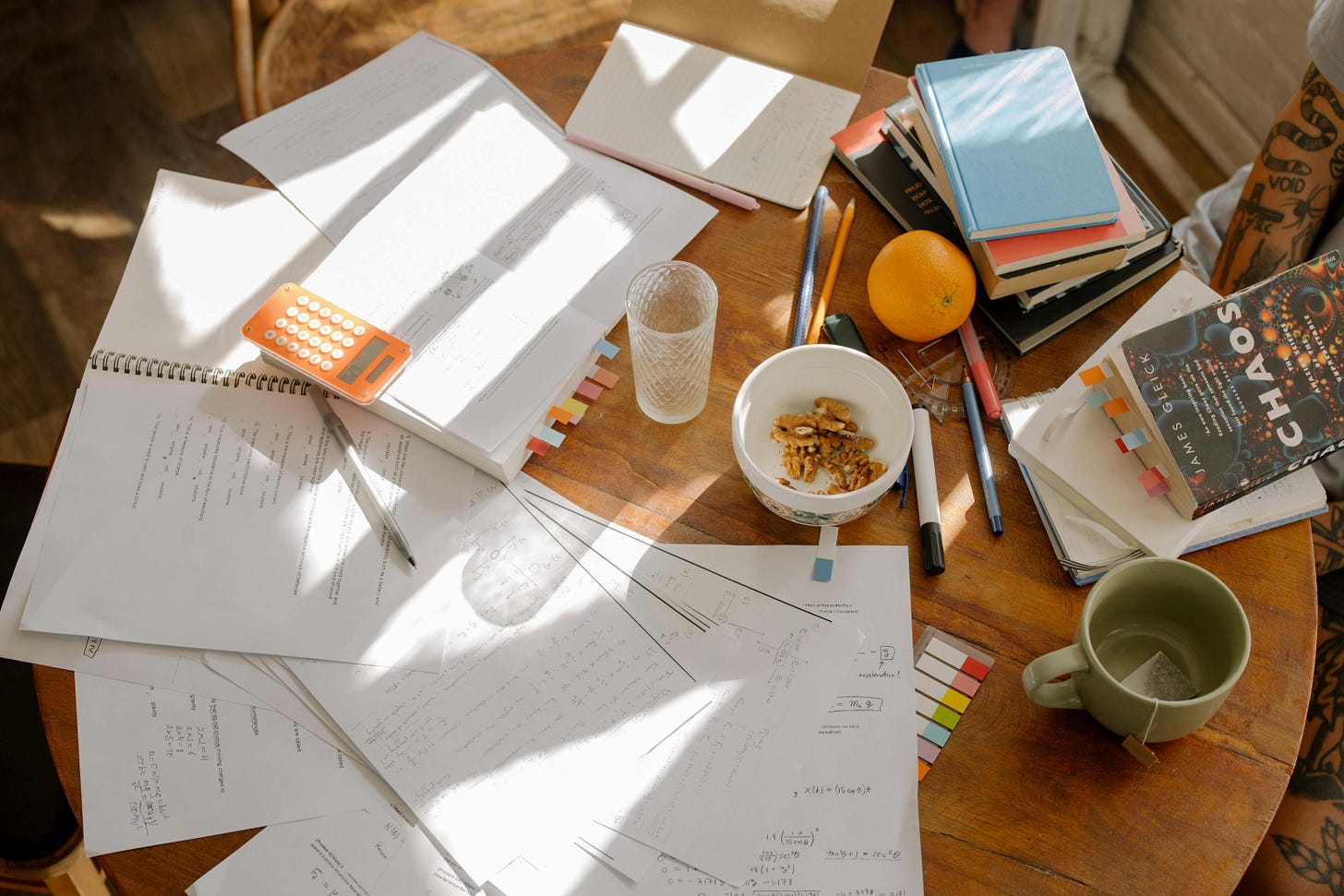

Why do we write? For fun? For profit? For catharsis? For vanity? For love? For validation? Probably all of the above and more besides. But as most writers will tell you, it’s hard work. Words do not normally pour effortlessly out of our heads like water from a tea kettle. It's more like squeezing juice from an orange—sometimes an orange that has already run out of juice or is so hard it refuses to relinquish any juice at all until you've almost given up hope, or an orange that is so slippery that it rolls away out of reach until we can find it again. This concerted effort to make sense of our thoughts and dreams, to translate these esoteric electrical impulses into legible sentences, makes writing so agonizing and yet so addictive to our curious and restless minds.

There is a stark difference between having an idea and actually manifesting it in writing. Everyone has ideas, but successful writers sweat and grind and persevere like linguistic masochists until the idea is living and breathing on the page and arranged just so. In his 2023 essay A.I. and the Fetishization Of Ideas, the author Chuck Wendig said that ideas are merely seeds that amount to nothing if they are not given life through the effort or struggle of writing execution. It’s the writer who turns the idea, no matter how vague or unoriginal, into something that might be worth reading. The end result—the output—is important, but so is the journey taken by the author to get there, just as the backstory of an artist and the origin of their philosophy or methodology adds to our appreciation of a painting.

Now that we live in the age of generative AI, writers are under attack from machines that have been trained on practically every novel and non-fiction book ever written, including many cases that infringe on copyright. Now anyone with an idea—stolen or otherwise—can generate an entire book, or indeed dozens of them, with a few chat prompts and push them to an online store where they will compete to take a portion of the profits that would normally be earned by legitimate authors. You can even ask the machine to copy the style of a particular author and it does a reasonable job of at least capturing the most obvious motifs and flourishes of each:

Okay, not perfect, but probably quite passable to anyone who isn’t a super fan. Notice how it has extrapolated Chuck Wendig’s use of disease metaphors? This mirrors his two most recent novels which center around a make-believe but eerily familiar global pandemic. When emulating Cory Doctorow it applies his signature techie lingo and preoccupation with internet security and the illusion of privacy found in so much of his work. For the Stephen King example, chatGPT imitates his knack for physical horror and uses the trope of a malevolent force in nature erasing humanity, leaving only a sense of nostalgia felt by the story’s protagonists who—like so many of King’s most memorable characters—are always looking back and contemplating their earlier lives. Finally, in attempting to sound like Mary Shelly it switches to the language of 18th-century romanticism, the gothic style, and uses anatomic metaphors that could almost be ripped from the pages of Frankenstein.

As a result of how easy it is to use free or cheap tools like chatGPT to produce completely boring and sometimes stupid but occasionally passable works of art, Amazon is being flooded with AI-generated fake books even at a time when more and more real books are being banned by right-wing NIMBYs. This disturbing dichotomy highlights something new and terrible that not only affects the economics of being a writer but I think poses an existential threat to the future of our culture: we are living in a world where an increasing number of human-made books are being banned and burned while robot forgeries quietly flood the market, turning authorship into an enshittified and ultra-commoditized race to the bottom. This puts ideas squarely at the top of the food chain and makes a mockery of the human effort we lauded at the beginning of this essay. I mean, if you have an idea and can just prompt chatGPT to write your book for you, why not? Why not forego the hard parts and skip straight to profit? That’s all that matters, right? There are some very enthusiastic YouTubers offering free advice on how to do this. Don’t forget to like and subscribe!

And herein lies the problem with the sudden surge and interest in artificial intelligence. AI-generated creativity isn’t creativity. It is all hat, no cowboy: all idea, no execution. It in fact relies on the obsession with, and fetishization of, THE IDEA. It’s the core of every get-rich-quick scheme, the basis of every lazy entrepreneur who thinks he has the Next Big Thing, the core of every author or artist or creator who is a “visionary” who has all the vision but none of the ability to execute upon that vision. Hell, it’s the thing every writer has heard from some jabroni who tells you, “I got this great idea, you write it, we’ll split the money 50/50, boom.” It is the belief that The Idea is of equal or greater importance than the effort it takes to make That Idea a reality.

— Chuck Wendig

Are you writing to share something unique and interesting and perhaps of value to others, or are you just writing as some sort of get-rich-quick scheme? This proliferation of dubious or outright nefarious AI-generated content has led to the coining of the term “AI slop.” AI may be one of the flag bearers of the so-called fourth industrial revolution, but to some unscrupulous bad actors, it’s just a new-fangled mode of distributing spam at a speed and scale that surpasses any digital scammer’s wildest dreams.

The marketplace for books isn’t the only vector for AI slop infestation: it’s also been reported on the blogging platform Medium, and some of Substack’s biggest newsletters rely on AI writing tools. This, to me, is the biggest insult to hard-working, honest writers: it’s not so much the international criminals who will do what criminals always do, but the talentless hacks who lean on AI to disguise the fact that they don’t have the skills, the patience, or the personal grit to become better communicators but will turn on subscription mode and take your money anyway, hoping you’ll never know they are purveyors of premium slop.

I’m not getting on my high horse and stating that I’m a judge and jury when it comes down to what constitutes quality writing—in fact, I encourage everyone to give it a try! We all start out sounding like Neanderthals, and it’s only through repetition, trial, and error that any of us graduate to Edward Bulwer-Lytton level or above. It’s also true that talent, taste, and quality are all subjective measurements, so if you’re brave enough to publish any of your thoughts at all in this crazy life, I salute you. But people who think they are writers by copying and pasting the output from a chat prompt? Give me a fucking break.

Congratulations. You said a thing and pushed a button and now the ART BARF ROBOT barfed art for you. Slow clap from the cheap seats.

— Chuck Wendig

Despite what the techno-feudalists masquerading as techno-utopian overlords and their unwitting fanboy army would like us all to believe, Large Language Models do not reason like humans, do not have any imagination, and cannot create novel art, despite the claims of some overzealous researchers. Therefore I refuse to take seriously any notion that we should accept or welcome books written entirely by robots. Do we really believe a book about being queer or one that depicts true stories of the American slavery era is more dangerous than The AI grift that can literally poison you?

LLMs recognize words only as numerical representations of characters, words, and phrases called ‘vectors’, which are multi-dimensional models of semantic meaning based on statistical correlation. LLMs are very good at using statistics and probability to estimate the most likely next word in a given sentence. I’m over-simplifying but that’s essentially how they work. It’s important to know that if anyone tried to convince you that LLMs think or reason like a human, or that a digital neural network is anything like a human brain, you’ve been lied to or have succumbed to another person’s ignorance on the matter. However, because they have been trained on such a deep, almost unfathomably vast corpus of text—more than any one human could ever assimilate in a lifetime—these uncanny machines are able to perform what some researchers have coined “the illusion of understanding.”

What we see when we interact with an LLM is a computer that seems to understand deep nuances that can surface complex layers of meaning in all manner of styles, voices, and formats. But because these machines appear like magic next to other technologies we take for granted, we commonly find ourselves in a state of awe when witnessing the results of our clumsy prompts: which leads to easy acceptance of the output. Simply put: during this experience, we are not exercising our critical judgment. LLMs are essentially a very clever parlor trick not unlike the Mechanical Turks of antiquity: they put on a good show and mesmerize us into believing they have achieved a certain level of accuracy through something akin to human reasoning even when that is patently not the case.

Consider the impact of the most powerful lever pulled by the snake-oil salesmen who peddle the miracles of generative AI: that it is personable by design. Something AI companies capitalize on with voice mode and integration with systems like Siri and Alexa, is the notion that LLMs like chatGPT and Claude are human-like but infinitely patient and tacitly submissive—the perfect willing partner to make you more productive regardless of the field you specialize in. It’s this intentional anthropomorphism that really does a psychological number on us—popcorn and fireworks bursting in our brains as we succumb to the fantasy that the machine really understands what we want. It’s always so civil and convivial. It lives to serve us, and will even lie if it has to. In stark contrast, search engines only give you breadcrumbs to what you want and then expect you to travel the last mile alone, while the human beings we encounter online can be difficult to engage with and all too easy to offend.

This sleight of hand helps to explain why so many writers today believe LLMs can be ideal creative writing assistants. But what use is a writing assistant that merely pretends to conjure up new ideas from the ether when it’s just regurgitating or plagiarizing material from authors who likely never gave the soulless simulacrum permission to use their work as a creative starter pack for other writers? And no, the way an AI “learns” from a large data set of published works is not the same as a human writer copying, emulating, or being influenced by the work of another writer, so let’s dispense with that false equivalence. Even if one can make the argument that using an AI assistant helps you individually as a writer—because you need it as a crutch or a way to break through writer’s block—I wonder if I might persuade you to consider that you’re just re-hashing ideas that have been published in the past, by writers who were better than you since they didn’t need to purloin from the assimilated patchwork of millions of other writers. You might also incorporate the fact that the LLM training models contain all manner of harmful racial biases that can’t currently be fixed. How would you feel if part of your legacy as a writer who uses AI is that you’re contributing to the potential end of creative diversification and the complete homogenization of online text? The silver lining for snarky Luddites like myself: you might also be contributing to the degenerative death spiral and eventual model collapse of the entire LLM training ecosystem. Ha!

If none of that gives you pause and you’re just rolling your eyes at me or looking for the ‘unsubscribe’ button, consider this: prolonged use of tools like chatGPT could result in loss of cognitive ability. In other words, there’s a good chance you could start out being a pretty good writer but get progressively worse the more you lean on AI tools. Which makes sense, right? If you sat in a wheelchair for 10 hours a day even though you were non-disabled, at some point you would lose muscle tone in your legs and you’d eventually be unable to walk without assistance. If you do use AI assistants in your writing or other work I don’t want you to panic: you aren’t going to suffer some massive and sudden brain atrophying event, but be aware that your brain might get lazy and forget how to perform some tricks over time if you keep outsourcing your thinking to the convenience machine. You might want to go on an AI diet and challenge yourself to use your own brain sometimes, even when it hurts a little. I envision a future where some people are going to make millions of dollars selling self-help books to help people wean themselves off these addictive tech toys.

I have more to write on this subject, but my fingers need a rest. Until next time, Thanks for reading!

As someone with both a mother and grandmother who had dementia and Alzheimer’s, I am all too aware of the cognitive delcine we can experience even without AI accelerating it.

It does have me asking a WHOE NEW SET OF QUESTIONS (c) what might be the replacement that takes up the voided space of our cognitive decline?

James, you raise some crucial points—what exactly is writing now?

Disclaimer: I'm a heavy GPT user. I use GPT to help me write almost everything, including my Substack posts. I sign them as "Directed by me, co-authored by my GPTs," because that's exactly what they are—GPT-generated text under human direction.

But it’s not as simple as “AI writes it, I post it.”

I give extensive in-session instructions, shaping tone, logic, and structure continuously. Over time, my GPTs have adapted to reflect my patterns of reasoning, phrasing, and framing. They don’t think like me (of course), but they’ve learned to speak like me—because I’ve trained them through recursive feedback.

The way I see it, GPT has taken over the “wordsmith” function—the intern, the assistant, the copyeditor doing the legwork. But I’m still the one who decides what the piece is about, what its function is, what it needs to do.

GPT is the pen. I’m still the hand.

And I think this distinction matters more than ever.