The importance of permanence

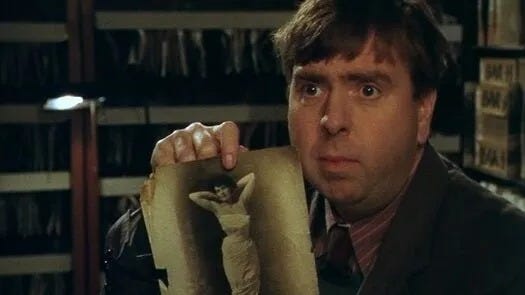

In the now ancient year of 1999 I had the pleasure of watching a dramatic miniseries on BBC television called Shooting The Past which was presented under the “Masterpiece Theater” banner, made famous years later by Downton Abbey. Starring the always excellent Timothy Spall and the inimitable Lindsey Duncan, the story of Shooting The Past unfolds over three episodes and concerns English museum archivists and curators in charge of a vast collection of black and white photographs that comes under threat by a big American corporation who want to destroy the collection and bulldoze the grounds to make way for a new business college on the land they recently purchased. The show centers around the museum workers who are going to be displaced, juxtaposed with the Americans who see shutting down the museum as a rather messy but necessary order of business.

I won’t give away the entire plot because I’m delighted to have rediscovered this gem on YouTube, and I highly recommend making some time for it. If you admire or love photography, this show will rekindle those feelings. But what makes it so relevant to today, and why it has always lived in a fond nook in my memory, is that it does such a wonderful job of a) slow, multi-layered storytelling without resorting to shock and awe, which is a rarity nowadays and b) the show’s message of respecting and preserving traditional photography serves as a wonderful reminder of how the ineffable magic of capturing moments in time on film has enriched our world. Thematically, Shooting The Past highlights the conflict between old-fashioned human values and the search for meaning versus the alien onslaught of the corporate profit-at-all-costs mindset. This has obvious parallels to the way in which AI companies today are encroaching on art and trying to commoditize it to the point of normalizing banality at an unknown cost to our culture and civilization.

I am not a photographer or any kind of visual artist, but I have a deep respect for all the humans who have, through the ages, memorialized our existence, our planet, and the objects in it on film, from Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype to the amazing photographers at National Geographic, and really anyone who ever took the time to point and click and create something to ponder, remember or just enjoy for the hell of it. There is something vital and humbling about traditional photography made without heavy use of digital post-processing. It has become integral to the experiential journey of our lives, it allows us to travel backward in time and has enabled us to document our history like never before.

What is a photo? What purpose does it serve?

Last week I attended an online talk by PHD researcher Bethany Berard (Carleton University) entitled: “On Believability: Photography and the Artificial Image”. In her presentation, Berard talked about how photography has always been a balancing act between evidence and art. On the one hand, a photograph depicts an actual time and place. On the other hand, the photographer has free reign to manipulate the environment or the models they are shooting in order to exact a more artistic scene. But, Berard went on to say, journalistic authorities and standards have long existed to identify and maintain a sense of what is authentic versus what is fabricated. For this reason, photography has become a “source of truth” in journalism and historical studies. This sense of integrity, she said, is being eroded like never before, now that AI photos are becoming commonplace and hijacking our perception.

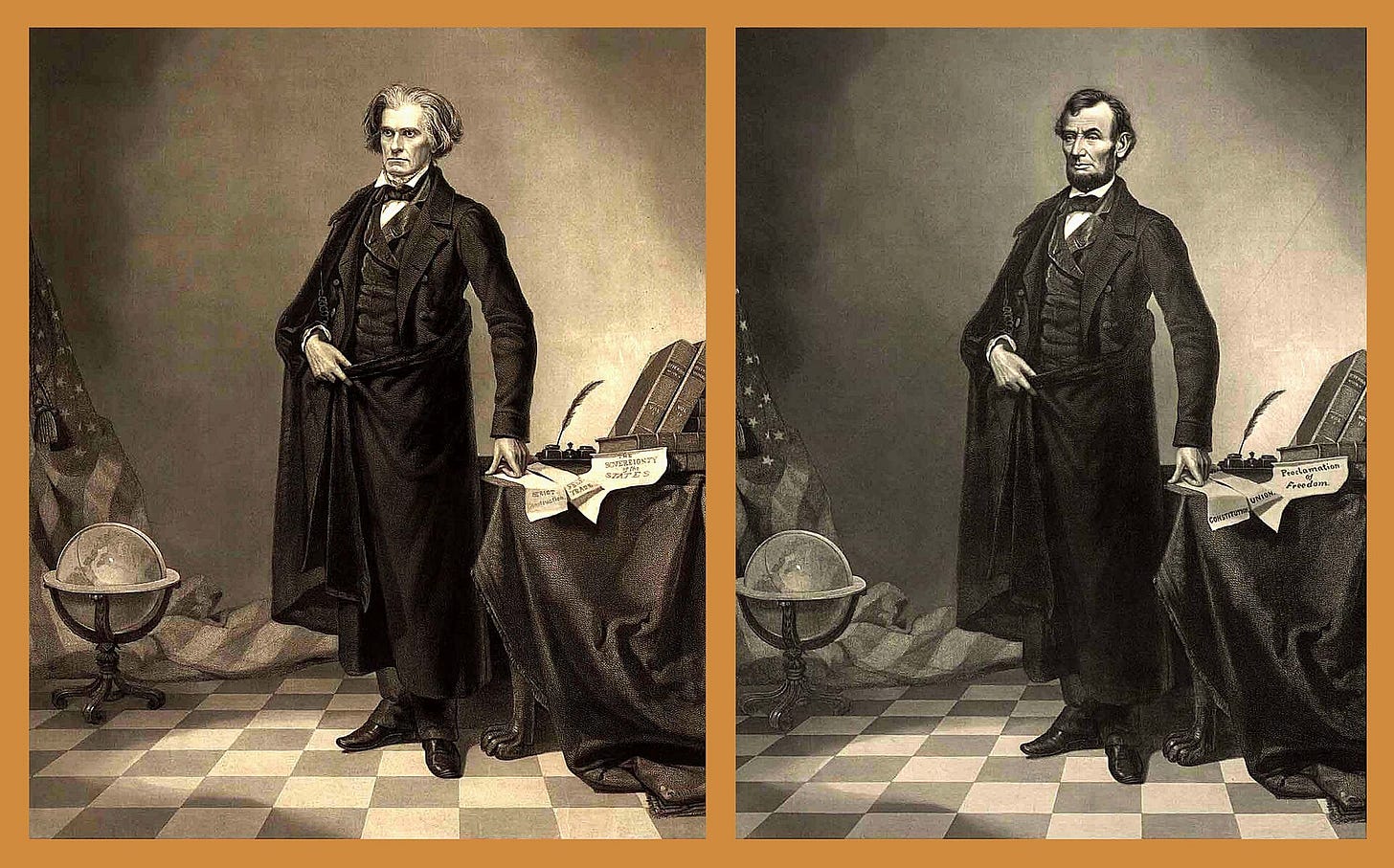

That is not to say that mechanical photography has ever been pure in the sense that it was not subject to bias or manipulation. It’s fascinating to me that not long after the invention of crude photography by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in 1826, amateur enthusiasts like the French photographer Hippolyte Bayard were already experimenting with different techniques to try to alter the original image, to layer on stylized imagery and metaphors. Bayard figured out a way to edit raw photos using certain chemicals inside a camera obscura to merge multiple exposures, an ingenious hack of a technology that was still in its infancy. His technique is perhaps best demonstrated by ‘Montmartre circa 1842’, where he inserted windmills into a photo of an urban street scene. Just because he could, I suppose.

Is there something innate in human nature that compels us to egotistically assert our own authority and meaning onto nature? Personally, I think so: it’s one of the core driving forces of all technological invention. But I digress. In approaching photography not as a way to document history or immortalize human vanity, inventors like Bayard unconsciously started a whole new aesthetic to compete with paintbrush art and paved the way for the world of photographic digital enhancement, repair, and manipulation that is commonplace today.

Since the advent of Adobe Photoshop and other digital photo manipulation tools, the job of validating what is authentic has become harder, and the rules about what makes a photo ‘real’ consist of goalposts that have had to be moved down the years. For a long time before generative AI even entered the public scene, Photoshop allowed the photographer to apply layering, cloning and healing, masking, digital painting overlay, texture mapping, and lighting and color correction to manipulate the original photo and enhance its qualities to fit a certain purpose or marketplace or convey a certain narrative with some artistic license. This has certainly had ramifications for how we perceive photography, but the advancement of this technology happened at a snail’s pace compared to the rapidity of generative AI progression. Society has had ample time to process what it means to be able to manipulate certain properties of a photo using digital tools, and how it changes our perception and understanding of the final product. But the generative AI revolution appears to be hitting us fast and hard with an affront to objective reality that we seem woefully unprepared for.

How much can a photo be edited in post-production before it is no longer considered a representation of real life? Before it is no longer even considered a photo? It seems that in most cases, authenticity is a matter of personal philosophy, though there are sometimes strict legal requirements that govern what is and is not considered valid. In the field of journalism, veracity is essential and uncompromisable, and in cases where the legitimacy of a photo is in question the news media sometimes pulls it from production, like they did in the case of Prince William’s faux pas earlier this year.

Into the void of the uncanny

Berard went on to talk about how AI-generated photos are now taking us into entirely new territory because, for the first time, anyone with access to AI tools can generate photorealistic images from just a few prompts. These are photos that were made without capturing any photons, without an aperture, without any exposure, without a human ever deciding what to include in the frame besides a few word suggestions to guide the machine. Just think about that for a minute: reality never played a part in these images, except insofar as they could not exist without the real photos they were trained on.

We are deep in the uncanny valley with regard to AI being able to generate photorealistic scenes, animals, objects, and people. I find that looking at an AI-generated photo makes me feel very uncomfortable, but I hazard to guess we’ll see this radar for the artificial diminished in younger generations, who will grow up with this stuff being normalized unless something happens to slow down or stall its proliferation. It’s also possible that generated photos will become so natural looking — for example: once it evolves enough to draw the right number of digits on a human hand and limbs with the right proportions — that it will be impossible in the future for anyone to tell a real photo and a generated photo apart.

Still, I feel a duty to point out that contrary to whatever AI evangelists like to say, generative AI is not creating anything new or unique or imaginative in any way, it is just regurgitating and hallucinating (a metaphor for random failure to produce expected results) different data distributions that build images pixel by pixel from billions of original images found in its diffusion training model. There’s a website that shows the supposed magical ability of generative AI to create realistic photos of people who don’t exist (refresh for new people, it’s weird) but there’s a counterpoint website where researchers are able to show that actually, the people who don’t exist are all based on real people who definitely exist. Peel back the curtain and there is always an underwhelming presence behind the great and powerful voice. Oh, and by the way, these tools may have been trained on your personal photos and the models contain many photos of children used without consent.

Generative AI startups and opensource code with no barrier to entry are quickly leading to the spread of AI slop photos on Google image search and social media platforms including Facebook, where nefarious scammers and unintelligent spammers have created fake photos depicting climate disasters or stupid hoax memes. Try searching Google images for “baby peacock”, then contemplate how our children are going to grow up in a world where the internet is more inaccurate and untrustworthy than ever before. And this being just the tip of the iceberg. What begins as a bit of fun has a tendency to become distorted and dangerous when new technology falls into the hands of bad actors. What started with Shrimp Jesus evolved in no time at all into inappropriate and illegal celebrity deepfakes. In my opinion, it was grossly irresponsible for companies like OpenAI and Midjourney to unleash this capability on the world without any warning or any attempt to work with governments and regulatory bodies in order to secure against at least some of the obvious negative effects it would have. Blame our current epoch of selfish and illogical late-stage capitalist nihilism. The light at the end of the tunnel is that according to some researchers, if the internet becomes completely filled to the brim with AI slop images, future AI models won’t be able to train on it because the ingestion of “synthetic” data causes it to go berserk and start churning out monstrosities. That would actually be quite an entertaining and fitting end to all this nonsense.

How it’s going

I’m tempted to say that for all of the AI hype over the past two years, and all the propaganda about how AI is going to transform every industry and propel the US national GDP to the moon, it seems to me that the most lucrative business built on AI so far is the deepfake scam. Tech-savvy criminals have taken AI photorealism to new heights and combined it with AI video and audio generation to create realistic human avatars that can appear in videos or speak on phone calls to dupe their victims into handing over money under false pretenses. These assholes target mostly older citizens who are less likely to realize they are talking to a non-existent person. According to the National Council On Aging, in 2023, deepfake scammers cost Americans $3.4 billion. But it’s not just old people who are preyed on, it could happen to anyone at any time, like the multinational finance firm employee who was tricked into sending $25 million to fraudsters who posed as his CEO.

We sorely need new laws and regulations to mitigate this fast-growing disaster, but the speed of innovation is now too fast for those sloth-like systems to keep up. Indeed, some photographers have already tried to sue AI companies for using their photographs without permission and failed because the courts are unable to understand that non-profit companies being leveraged by for-profit companies should not be a loophole around copyright. I don’t want to veer into a larger discussion of AI art in all its variations right here but will mention that, conversely, some ridiculous prompt artists are trying to argue that their AI slop should be awarded copyright even though they know full well that their “art” is plagiarism at best. For those curious about where the legal narrative goes next, the case to keep an eye on is Getty vs Stable Diffusion.

Things are already weird, but they’re about to get weirder. It isn’t just software like Photoshop and new tools like Midjourney and Dall-E that are taking us down this path where photos no longer have any authenticity or integrity, it’s increasingly built into the hardware. Chances are, your point-and-click camera already has AI built in that long precedes the generative AI I’ve been talking about in this essay. Anytime you take advantage of automatic focus you are activating mechanisms that are based on machine learning algorithms. And functions like red-eye reduction, multi-shot, and automatic day/night aperture settings have been around for at least a decade. The human makes the decision to click the button but the machine decides precisely where to look. Some newer cameras include the ability to automatically focus on certain aspects you want to capture in a given scenario, such as being able to target the eyes of a bird when you’re bird-watching. Some cameras even have the ability to track where your own eyes are looking in the lens view or to track and stay focused on whichever objects you specify even while they are moving. This all relies on deep learning and object recognition algorithms and even I would say this is kind of cool and probably really helpful and appreciated by many photographers. And depending on how philosophical you are about what makes a photo “real”, probably not anything to complain about. Puritans can always choose to shoot in manual mode and save in RAW format.

In the end, to what end?

But what about the camera on your smartphone? Iphone, Google Pixel, and Samsung Galaxy are leading the field in packing new AI photo features into their phones, giving users magical abilities to distort reality in ways we couldn’t imagine just a few years ago. Don’t like the color of those clouds? Change the background to a sunset instead of an early afternoon. Random stranger accidentally photo-bombed your pic with mom at the National Park? Just highlight to remove them and an algorithm will seamlessly fill in the missing pixels with what should probably be there based on what it has extrapolated from the rest of the photo. Again, pretty cool at first glance. But what kind of habits are we now forming? It’s already bad enough that social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram have become incredibly performative, full of people posing as if they lead perfect lives, causing the less endowed to feel like unworthy failures. Now everybody who can afford the best phone will look even more perfect and happy than ever. But we’re only lying to everyone, including ourselves.

Some camera enthusiasts say that even the basic default processing algorithms on point-and-click cameras and smartphones are too much and that for anyone who actually wants to learn the skill of taking photos you need a device that doesn’t come with training wheels and magic fairy dust. Even beyond the new AI magic, cameras and smartphones have features like automatic light adjustment and HDR enhancements that hardcore photographers want to disable, which is why there is now a steadily growing market for things like the Process Zero app for iPhones. I also think that for some people, this is a pushback on generative AI and surveillance capitalism in much the same way that Gen-Z is rejecting smartphones altogether in favor of dumbphones. The same pushback has spawned grassroots initiatives to combat AI forgery and AI slop and to reclaim rights for authentic creations, such as the Content Authenticity Initiative and the stated mission of the Human Intelligence Institute. These are really interesting developments in our culture and something that speaks volumes about how tech companies really don’t understand their customers as much as they claim to.

Like the protagonists of Shooting The Past, we have to acknowledge that what we once held to be true, sacred, and worthwhile in our lifetime is under threat from corporations who will choose profit over human provenance. Unlike the bad guys in that story, the people who now have an outsized impact on the future of our species are toxic, disassociating billionaires who will gladly lay waste to art and culture in order to win the game they are playing in their own narcissistic and megalomaniacal imaginations. What’s worse is that many people lionize these leaders and are currently under the thrall of AI and have invited it into their homes and their lives without stopping to consider the risks and consequences and how they are only helping to empower these misguided techno-fuedalistic overlords to gain even more power over us. And if we stay on this trajectory I fear we are going to lose a lot more that is precious to us than we stand to gain.

I wonder if anyone already has a framed photo on their mantelpiece or in a family photo that was generated by AI or at least manipulated by AI or retouch tools? If not now, it’ll happen soon enough. What sort of legacy will we be passing down to the next generation as a keepsake or a historical record? Will tomorrow’s chroniclers be able to look back at photos of the 21st century and be able to say that they fairly represent the reality of those times? Will our grandchildren scratch their heads and wonder, were my parents really that well-proportioned and young-looking in their middle age? Was my hair really that bright in the sun? Were my eyes really so sparkly? Was the house ever that tidy? Did my parents really take me to Paris when I was two, and was that tiger in the zoo really so gigantic? How come Uncle Jack is not in any of these pictures? Or Cousin Mary? It’s like they never existed, why? Why do I remember Dad standing next to his old junk of a car in this photo but now it shows a shiny Mercedes I don’t even remember? Did people used to pray to a crustacean deity? Did the Pope play baseball, or wear a puffer jacket? Did children ride giant turtles (now extinct for this far-flung descendent) for fun? If photography is no longer a source of truth, will any of the truth survive? Was it worth it to automate human creativity until it was nothing more than a vestigial function lying dormant in our atrophied brains?

Say cheese!

Brilliant post Jim, full of wonderful insights and observations. Going to quote this: “I feel a duty to point out that contrary to whatever AI evangelists like to say, generative AI is not creating anything new or unique or imaginative in any way, it is just regurgitating and hallucinating (a metaphor for random failure to produce expected results) different data distributions that build images pixel by pixel from billions of original images found in its diffusion training model.”

Insightful article. Big fan of AI baby peacocks.

A practical consideration: Some of these initiatives to 'counter' the AI trend seem rather counterproductive. If you label your work as 'Zero AI', you all but ensure its usage in the next batch of training data. The scrapers will thank you for your help (while maintaining plausible deniability, of course).